Even on a mountain, there’s always something to look up to (Photo credit: Pudkrong Kaewpichit)

Long before reaching our final destination, the Himalayas start to blanket the horizon. It’s a bird’s eye view of what will become the backdrop of our lives for the week to come. Smoothly, our plane glides between the peaks and aligns itself with the lone runway of Leh, nested in the valley below. At an altitude of 3,500m, Leh is the economic and political center of the region of Lahakh and host to its only civilian airport.

Spilling out on the tarmac with us are about a hundred other tourists. Most hail from other parts of India. With them, they bring families seeking reprieve from the 45°C weather dominating the more southern parts of the country. Part of our destination’s apparent popularity may be due to Indian school holidays being in full swing.

Western tourists are few and far between. A lawyer, the only other German tourist I bump into, says he wouldn’t have known about the place until he saw it mentioned in a documentary on a French culture niche TV channel. There is one group of foreign tourists who don’t need to turn their TV to an art documentary to find out about this place. Wherever we go in Ladakh, we run into Thais. At the airport. In the hotel lobby. At the breakfast table with their culinary first aid kits (chili sauce, mama noodles, dried shredded pork and seafood sauce). Nowhere to be seen are the customary tour group leaders who usually funnel them into commission-based souvenir shops. According to the owner of one guest house, up to 70% of his guests were Thai.

Cheesy prayer flag shot? Cheesy prayer flag shot!

At this point, I need to admit that the idea for this trip came from my girlfriend who, well, is Thai. Unbeknownst to me, Ladakh has become a well-known tourist destination in Thailand’s Facebook community. Social media users praise it for its cold weather and crisp air, cheap flights connecting Bangkok (with a stop-over Delhi), and a tourism industry that’s touted as, well, tout-free. Few tourism promotion agencies could compete with what travelers have accomplished for the region on Instagram and Facebook.

It may be that the reason for an abundance of Thai visitors lies closer to the ground. Not a stranger to squatting toilets, Asian tourists might have less of an issue putting up with some of the more rudimentary aspects of Ladakh’s infrastructure. While there are modern hotels, many stops along winding mountain roads require a bit more flexibility in the attitude and knee joints of travelers.

On my travels, I’m usually not overly keen to connect with other tourists, making these considerations soon take a back seat. Replacing a rest day with an extra dose of altitude sickness pills, we opt to explore the town’s sights after checking in and a quick morning nap. The warm afternoon sun gives us a few hours before having to face the cold reality of a guest house devoid of any heating. Locals were out and about in their down jackets since the sun was up. They didn’t seem to mind or notice temperature changes to the degree (ba-dum-tsh) we did.

A young girl in the remote village of Turtuk, the last settlement before the Pakistan border that’s open to visitors. (Photo credit: Pudkrong Kaewpichit)

Sights in Leh are impressive, but nothing to behold compared to what would follow. Not having checked out the travel forecast known as Google image search, I revel in the landscape surrounding the city. Stupas, monasteries and an old palace grace surrounding hills and mountainsides.

On our second day, we set out to reach Nubra Valley. Visiting a neighboring valley might not sound like much of an excursion, but the thing with going from one valley to another is that there’s a non-valley-thing in-between. In this case, it’s Khardung La. At an altitude of 5,602m or 5,359m (depending whether you place your trust in the local tourism authority or your GPS equipment), it idles at the top of one of the highest roads in the world.

A concerned-sounding, hand-written warning urges travelers to not remain at the top of the pass for more than 25 minutes. With the souvenir shop not having awakened yet from the slumber that carries it through a minus 40°C winter, there’s little reason to do so. The restroom up here has a nice view. It doesn’t have any walls though. Or anything else really. In fact, while a building with a ‘restroom’ designation exists, it’s locked and everyone makes do with the ledge behind it, reducing the buildings functionality to an outdoor partition.

Sloping down from the peak of India’s infrastructure, we enjoy a stunning mountain panorama. The soundtrack to potholes interspersed with gravel comes in form of a Buddhist prayer song originating from the driver’s USB flash drive. Seeing how he drives when a more upbeat song comes on, I regret not bringing any more spiritual tunes myself.

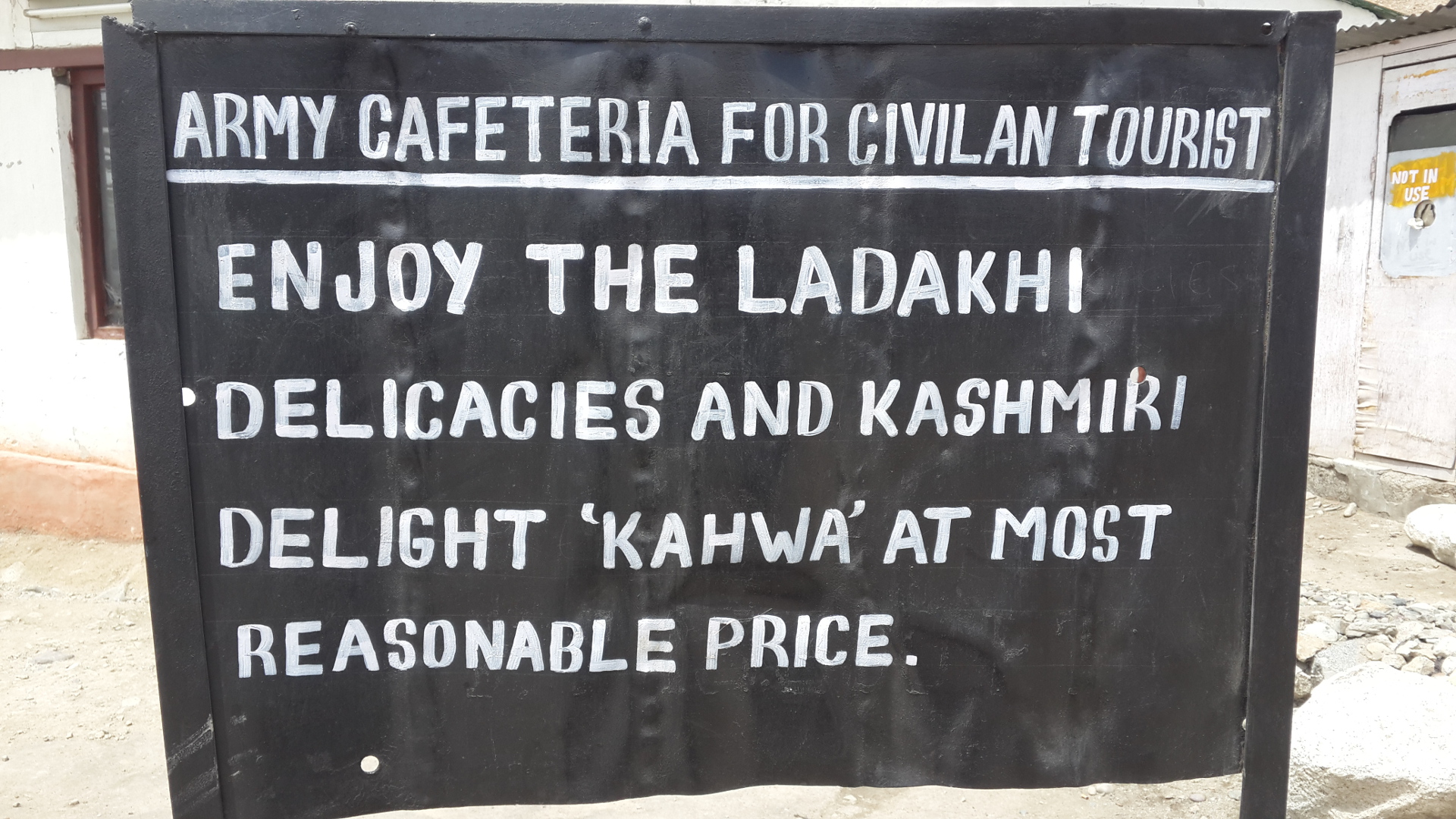

With that sign they could have charged $5 for tap water and I would have bought it anyway.

At the foot of the mountain pass on the other side lies the first of many military bases to come on this trip. A crudely painted sign advertises tea in the military cafeteria for USD 0.15. Good enough of a reason to make a quick stop. The soldier on duty pours me a cup of hot and sweet. A perhaps overly optimistic inquiry about a toilet nets me the reply that this is the military and civilians are across the road. Deciding that this wasn’t intended to be a social commentary, we cross the road to track down a restroom operated by Ladakh’s commercial sector.

Intertwined lives of soldiers and civilians here are the norm. One of our drivers puts on a uniform at the end of every tourist season, joining the military to drive trucks until the next season starts. In a region of the world where three nations share nuclear armament and appear divided over pretty much everything else, there is no shortage of military job openings. The perpetual presence of the Indian armed forces strikes me as the primary reason for a lot of the infrastructure.

This is far as the soldiers allow you: The village of Turtuk. (Photo credit: Pudkrong Kaewpichit)

The people around here who don’t scrape a living from the mountainside by driving tourists or guns around include livestock herders that roam the valleys for its scattered spots of green. The harsh environment doesn’t support much: A sturdy selection of goats shares the landscape with a scattering of yaks and the occasional horse.

One such goat herder we pass on our excursion to Pangong Lake a few days later on. It’s by far the most popular destination in the region. The same person set against a city backdrop would make me think them homeless and at their lowest point in their life. In a way, that might even hold true in this case. But in these mountains, even low points are fairly high up.

Pangong Lake. There’s a reason they shot a movie here. (Photo credit: Pudkrong Kaewpichit)

Pangong Lake itself comes into view as a speck of unnatural blueness two hours later. This inland saltwater lake has played host to Bollywood blockbuster ‘Three Idiots’ in 2009. As a result, it has been rediscovered by local tour groups who act out ‘Three Idiots’ movie scenes on the beach and drink tea in ‘Three Idiots’ themed coffee shops. The number of actual idiots we encounter thankfully remain in the single digits. On a whole, both locals and visitors are considerate and treat it each other well. It’s something I often miss at prominent tourist locations elsewhere. That doesn’t mean there aren’t exceptions.

Our driver is eager to get home. He has a family waiting for him back in Leh. He’ll have a few hours at home before having to head out for the next tour tomorrow morning. On the way back, we pass the same goat herder. This time, the shepherd’s dogs take offense to us passing the herd, and their angry barks zero in on us. The barks turn to yelps. I turn around in my seat and spot a limping canine. Did we just hit him? I’m not sure. It pains me to think about it. Did our hurried passing just result in an injured dog? How much of a loss would that be for the shepherd? How resentful does the shepherd feel? All these cars driving by, anywhere between a nuisance and a threat to her livelihood and the well-being of her animals.

#samsungs4 #nofilter #goatstagram … or: time to buy a proper camera

Reflecting on the moment, I can’t help but wonder if making him stop the car and check in on them would have been my responsibility. It seems to be the right thing to do. But the moment passed, and I say nothing. Is that what happens when tourism and nature collide? A moment of questioning, followed by a brief silence and, ultimately, regret in hindsight?

As striking as the scenery may be, the region lies at the outskirts of human civilization itself, and border skirmishes with nature do happen. On the last part of our drive back, I spot the wrecked remains of a military convoy, scattered on the slopes of the famous Chang La mountain pass. Having fallen victim to an avalanche last year, these now remind tourists that our stay here is limited to a brief summer before the snow reclaims its lost territory.

As our flight accelerates on Leh’s runway, I can’t help but wonder what will become of this region in years to come. Will its people reminiscence about today as a more simple, worry-free past? Will they see it as a time fraught with birthing pains of an industry that increased their quality of life? Will they see it as a beginning of an end to traditional values, a time when nature was still intact and when people hadn’t been corrupted by the allure of easy tourist rupees? Or are we long past that point?

Want to visit Ladakh yourself? I’ve put together an in-depth guide to anything from altitude sickness pills and a detailed budget breakdown to negotiating car hires and getting visas in this in-depth guide to traveling in Ladakh.

People seemed blissfully unaware of the tree of life. Yay for easy people-free shots.

Looks amazing – shame my Thai girlfriend has no interest in visiting India, will look through your guide see if I can get her to change her mind!

To be honest – I wasn’t exactly thrilled about the idea either, possibly for the same reasons. I always associated India with a lot of hassle – lots of negotiating, dual pricing, much smaller personal space, and health concerns. However, Ladakh is really something different from the usual India experience and while I still have an uneasy in my stomach about repeating trips to other parts of the country, this area I feel confident in endorsing.